When we understand life’s adaptations to the changes brought by fire, we learn to value disruption as a path to resilience.

Fires are fundamentally a natural force, shaping and rejuvenating ecosystems by clearing debris, enriching soils, and stimulating new growth in newly transformed geographies. For hundreds of thousands of years, humans have controlled or intentionally set fires both small and large to manage the openness of landscapes, the growth of plants, and the movements of animals, often promoting overall ecological stability and . However, the last century saw a stark shift. Around the globe, intensive management practices—aimed at suppressing wildfires to protect human interests—have disrupted the natural balance. By extinguishing smaller, regular fires, we have created a situation in which forests have grown denser, accumulating more combustible materials. Now, when fires occur, they burn hotter and more intensely, often leading to catastrophic outcomes for humans and the rest of nature in wild, rural, and even urbanized areas.

This has led in part to what historian Stephen J. Pyne has characterized as the Pyrocene, a geological epoch shaped significantly by fire, paralleling the influence of the Anthropocene. Pyne suggests that human activity, including extensive use of fire for agriculture and industrialization, has intensified fire activity globally. This fire-driven era influences ecosystems, climate, and even species evolution.

Wildfires are not isolated events; they are deeply embedded within “complex socio-ecological adaptive systems.” These systems are intricate networks where ecological and social components interact, adapt to changes, and evolve, in cycles consisting of four phases:

Growth. Conservation.

Release. Reorganization.

Drawing inspiration from these insights, in 2024, The Institute gathered a diverse group of nature-inspired scientists, engineers, designers, artists, and architects in a larch forest in the Northern Rockies. Together they embarked on a journey to reimagine their disciplines through the lens of wildfire resilience. They looked to nature’s resilient species—such as trees with pine cones that release seeds after intense heat, and tortoises that create fire-resistant burrows—as models for fire-adaptation-inspired technology, design, and systems.

Examples of these technologies already abound: biomimetic materials that resist fire and insulate living tissue from heat, architectural designs that employ natural ventilation systems to prevent fires, and urban planning strategies that embrace green corridors and fire-resistant landscaping.

Beyond technology, there are broader lessons to be learned. Rituals, practices, and belief systems surrounding fire speak to a deeper connection with the natural world, emphasizing respect, balance, and community stewardship. These rituals offer a framework for contemporary societies to reevaluate their relationship with fire, moving from fear and suppression towards understanding and collaboration. Indigenous communities within fire-shaped bioregions have also coevolved with fire, creating deep and reciprocal relationships. This is seen, for example, in the way Aboriginal communities continue to work with fire to shape the terrain, optimize food production, and strengthen their endemic relationships to land.

As society grapples with the increasing reality of wildfires in a changing climate, embracing wildfire resilience means not just adapting technology and management practices, but fostering a cultural shift. It entails honoring the role of fire in natural ecosystems, integrating Indigenous wisdom into contemporary approaches, and fostering a collective responsibility to coexist with wildfire as a natural phenomenon. In telling the story of wildfire’s lessons, the aim is to inspire a paradigm shift towards a future where human and ecological systems thrive in harmony with fire’s regenerative power.

This journey is not just about mitigating disaster but about rekindling a profound connection to the natural world, acknowledging that our well-being is inextricably linked to the health of the ecosystems we call home.

Fire Ecology Primer

The words we ascribe to fire are significant. In the English language “wildfire” conjures an image of fire burning out of human control. And there are various words that come to the forefront when thinking about the causes and effects of fire:

Cleansing. Conflagration.

Devastation. Blaze.

Inferno. Burning.

Kindle. Spark.

Modern technology carries fire’s legacy in both its inner workings and in the words we retain to describe them:

We burn CDs,

deploy firewalls,

ignite engines,

and light up bulbs.

But fire holds its most significant role in the rest of nature and in life. In fact, there would be very little fire without life, because living things produce most of the materials that extreme heat causes to burn. We may think of fire as elemental, but heat or energy is the real fundamental aspect of it, and the flames are the result of an amalgamation of elements interacting. Life’s processes combine matter and bind up energy, storing it in complex compounds. When this material heats up, it can burn, breaking chemical bonds, releasing gases and energy, and resulting in ashes––a complex, catalytic process needed to cycle energy through an ecosystem.

Even ecosystems with a very low frequency of fires are categorized as fire-dependent. A bioregion-defining force, fire shapes the trajectories of economies and influences the lifecycle of civilizations. Fire is then one of life’s throughlines––affecting others and effecting change.

Fire within an ecosystem exemplifies an adaptive cycle––a concept central to our group’s work. For an example, let’s look at a forest ecosystem. The adaptive cycle begins with a growth phase, where species rapidly colonize available space and capture resources. During the conservation phase, these resources become increasingly locked up in established organisms and complex relationships: nutrients get bound in living tissue, food webs become intricate, and the system grows more efficient but less flexible. When the system becomes too rigid, any significant disturbance—whether disease, weather, resource scarcity, or fire—can trigger the release phase. This disruption breaks down the accumulated structures, releasing stored resources and creating opportunities for change. In the reorganization phase, surviving species and new arrivals begin to capture the newly available resources, experimenting with new combinations and relationships, and the cycle begins again with renewed growth.

Fire Succession and Disturbance

Fire succession is the cyclical process through which an ecosystem recovers and regenerates following a wildfire. It begins with the initial disturbance of the fire, which clears away vegetation and alters the soil. In the immediate aftermath, pioneer species such as grasses and forbs, like fireweed, quickly colonize the bare, nutrient-rich soil, stabilizing it, which makes the ground suitable for more complex plant communities. Over time, shrubs and small trees establish themselves, leading to the gradual reappearance of a mature plant community. This progression continues until the ecosystem reaches a stable, climax state, where species composition and structure resemble those present before the fire, but often with enhanced biodiversity and ecological resilience. It highlights the dynamic nature of ecosystems and their ability to regenerate through a series of predictable and adaptive stages.

A fire is a powerful disturbance, and depending on its severity and scale, may tip an ecosystem into the adaptive phase called “release.” By release, we mean a disruptive phase where resources are released through disturbance (e.g., fire, financial collapse). In an ecosystem where the fire regime is allowed to cyclically burn instead of being suppressed, the system is able to maintain its resilient state and recover from the disturbance while maintaining most of its material in its current state or form. If a fire regime is suppressed, the potential of severity increases, making a fire event more likely to trigger release––where a vast amount of stored matter and energy is broken apart and returned to more simple states and forms. What can we learn from this?

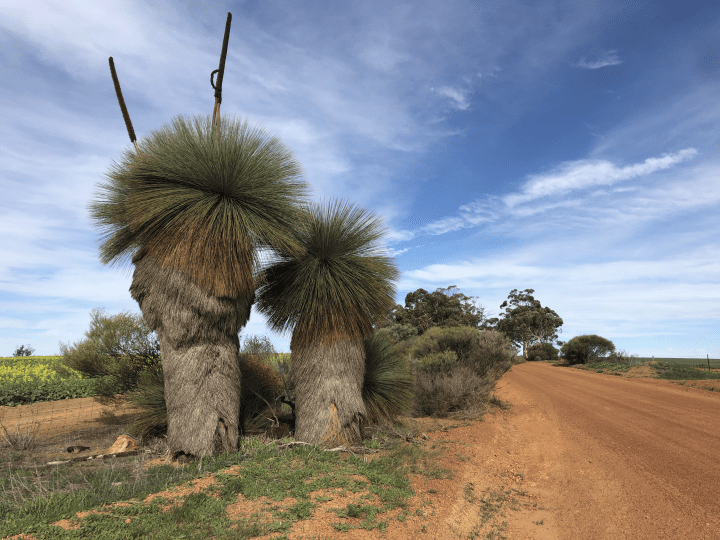

Just as different communities have different relationships to fire, so does each organism within the ecosystem. Species experience fire from vastly different perspectives and scales, and we seem to be alone among them in our goal of suppressing or extinguishing its existence. Some species rely on fire to trigger life-cycle events like germination and reproduction, while others take advantage of the post-fire regrowth and low competition for food sources. Some have adapted to the fiery landscapes through heat resistant scales, hides, and barks. Still others build or utilize communal fire-proof tunnels and mounds, and clonal plants develop under the surface root systems ready to regrow once the blaze has passed. This diverse roster of s shows us not one right way to relate to fire, but many––as diverse and unique as the bioregions, communities, cities, and civilizations present on this earth.

After a wildfire, the recovery is shaped by the larger system’s memory of past disturbances and its ability to reorganize in a resilient way.

Wildfire Adaptations as Model, Measure, and Mentor

Model: Emulating What We See

Complex socio-ecological adaptive systems are characterized by the interconnectedness and interdependence of the activities of humans and the rest of nature. These systems are complex because they involve multiple interacting components that can lead to unpredictable behaviors and outcomes. They are adaptive because they respond to internal and external changes through feedback mechanisms, learning, and adjustments. The actions of humans, such as land use, resource extraction, and policy-making, directly influence ecological processes, which in turn affect human well-being, creating a feedback loop.

In these systems, resilience, adaptability, and non-linearity are key concepts to understand the framework of panarchy––the interconnected, dynamic cycles of growth, accumulation, restructuring, and renewal in natural and social complex adaptive systems.

A key insight of panarchy is that the resilience and adaptability of a system depend on its ability to navigate these cycles at different scales, both temporal and spatial, offering a valuable lens for organizational and societal structures by highlighting how systems adapt and transform through interconnected cycles of growth, collapse, reorganization, and renewal. By mimicking nature’s balancing act, structures can evolve, remaining resilient amid the pressures of both ecological and economic change.

Measure: Meeting Ecological Performance Standards

Fire-adapted ecosystems illustrate how natural systems flexibly respond to disturbances over time. Species within these ecosystems have developed specific traits that allow them to thrive despite periodic fires—like the thick bark of ponderosa pines, which protects them from low-intensity burns, or the rapid resprouting capacity of chaparral plants. This adaptability reflects principles of complex adaptive systems, where components (species) continuously interact with and respond to environmental changes, producing dynamic patterns at multiple scales.

In a complex adaptive system, each component affects and is affected by others, creating feedback loops that make the system resilient to disturbances. In fire ecology, the adaptive cycle models this process, where ecosystems move through phases of growth, conservation, release, and reorganization. For example, frequent, low-intensity fires may prevent excess fuel buildup, preserving ecosystem stability. However, if these fires are suppressed (short circuiting the system’s typical feedback loop), fuel accumulates, making the system more vulnerable to large, destructive fires.

Mentor: Learning From Controlled and Managed Disruption

Lessons from fire ecology offer profound insights that can be applied to human endeavors like innovation, policy-making, and organizational structures, particularly in the areas of adaptability, resilience, and the management of disruption. In wildfire-prone ecosystems, fire is often a natural and necessary part of the cycle, clearing out dead vegetation and making space for new growth. Fire-adapted species thrive on this process, illustrating the power of resilience through renewal. Similarly, in human systems, disruptions such as economic shifts, technological breakthroughs, or societal changes can innovation and creative problem-solving. Rather than fearing or avoiding disruption, businesses and governments can design resilient systems that thrive because of it. Disruption, when properly managed, becomes a driver of long-term growth and creativity.

Disruption also makes us think of our view of time in a way that is not linear as in the take-make-waste chain, but cyclical, with periods of growth, conservation, release, and reorganization.

Diversity plays a central role in both ecological and human systems. In fire-dependent ecosystems, biodiversity increases the system’s resilience. For human endeavors, this lesson underscores the importance of fostering diversity—whether in perspectives, skills, or business models. Just as ecosystems rely on a mix of species to weather disturbances, diverse teams and industries are better equipped to navigate uncertainty and change.

Fire ecology teaches the value of controlled disruption. Prescribed burns, used to manage wildfires, mirror natural fire cycles and prevent larger, more destructive fires. This principle can be applied to innovation and organizational management, where controlled experimentation or phased projects allow for testing new ideas with minimal risk.

Through the lens of fire ecology, human systems gain a new perspective on resilience, using the dynamics of wildfire to evaluate strategies for adaptation, self-organization, and community-wide stability:

- Embrace change.

- Adopt a cyclical view of time.

- Consider the broader socio-ecological system.

- Consider impacts and adaptations across scales.

Reimagining Our Relationship with Wildfire

Wildfire teaches us that resilience is not found in rigid control but in adaptability, diversity, and mutual dependence across scales—whether in whole ecosystems or in human communities. Embracing this perspective often requires a shift in how we view change; rather than resisting it, we must recognize disturbance as a force that strengthens and renews.

This journey toward resilience is a call to action, urging us to align our systems with the natural rhythms that foster stability through dynamic balance. By taking cues from fire-adapted landscapes and species, we can build communities, organizations, and policies capable of thriving amid uncertainty. Just as fire clears the way for new growth in a forest, challenge and disruption can be catalysts for positive, sustainable change in society.

By seeing adaptations to wildfire as model, measure, and mentor, we gain the tools to see ourselves as part of an adaptive, living world where we thrive not by control but by collaboration and embracing the natural, fiery cycles of disruption and renewal.

This collection essay is based on foundational work by the 2024 Biomimicry Launchpad cohort, especially Rae Lewark, Joe Cardielo, and Dave Hutchins. It has been edited for clarity and length from a technical report––created by the aforementioned group––by Jenélle Dowling, Lily Urmann, Andrew Howley, and Camilo Garzón.